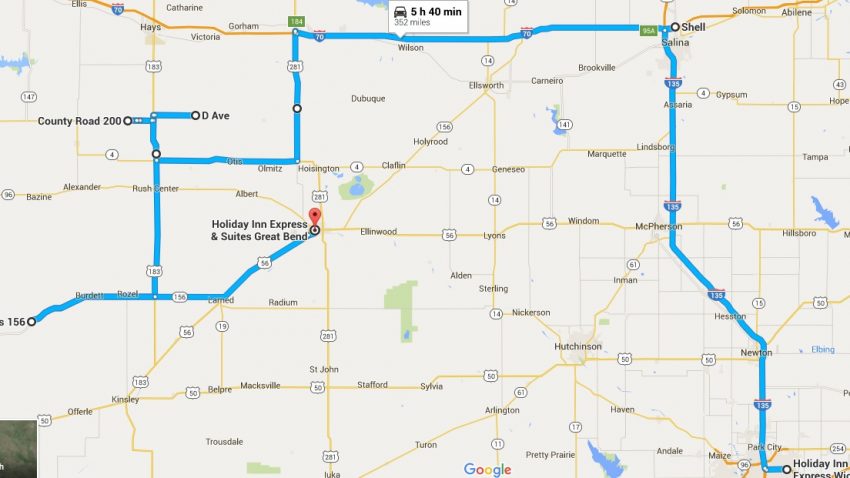

Models indicated this morning that a much deeper surface low would coalesce by the afternoon as a shortwave ejected northeastward along an upper-level trough. This low would be the deepest and most organized of the trip, and as a result the most well-defined warm front of the trip would be in play. These warm fronts are important because, like weaker outflow boundaries, they provide an axis along which low-level winds back and improve the overall shear profile. This warm front would provide a more focused area for rotating supercell and tornado development. Since the surface low was expected in southwest Kansas by the afternoon, the warm front was expected to drape along the Nebraska-Kansas border, and our target was north central Kansas. We decided to move to Salina for another look at data and make futher decisions about our target.

11 AM CST mesoanalyses and radar analysis combined with surface observations indicated clear mositure wrapping from the south counterclockwise around the low through north central Kansas. The axis of this moisture wrapping was centered on Ellsworth, KS. The 11:30 SPC convective outlook update upgraded central Kansas to a moderate risk with a 15% chance of tornadoes and a 10% chance of EF-2 TO EF-5 tornadoes. Satellite and radar observations indicated boundary interaction near Russel, KS. We targeted that city and moved to wait for initiation.

12:30 PM CST initiation in southwest Kansas outside of our target area quickly became messy and numerous due to a very weak cap over the region. This brought concerns for our target area, as early convection could stabilize the atmosphere enough that later convection could struggle to initiatie. We became uncertain about the severity of the day, which turned out to be warranted.

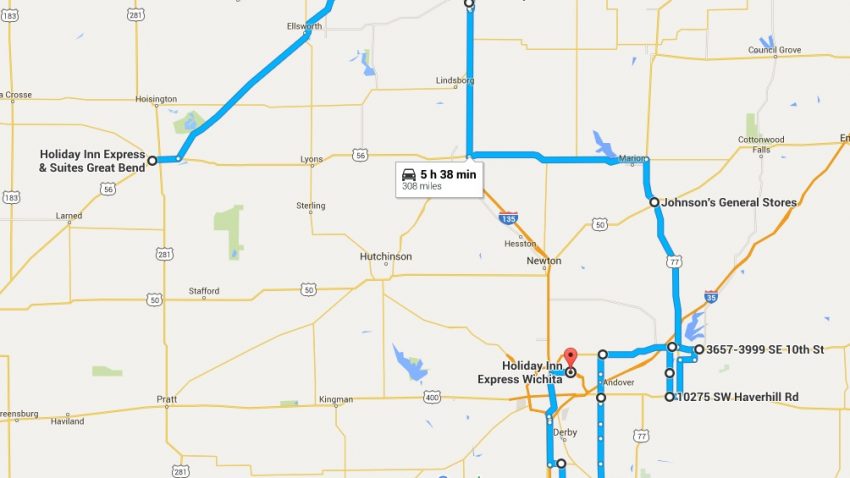

We decided to intercept a storm just north of Jetmore that had initated to the southwest of the target region. We chose this storm because the larger storms to the south were entering a cloudy environment that convection had already been present in. The Jetmore cell was entering a clear area, and was closer to the boundary so better shear was present. The storm ended up fizzling, but the larger storms to the south were moving north into a boundary, so we moved ahead of them to attempt an intercept, even thought the storms were non-rotational. Road conditions quickly deteriorated, and we were left with no clear escape route. The storm’s shelf cloud overtook us (Figure 1), and we got deluged on.

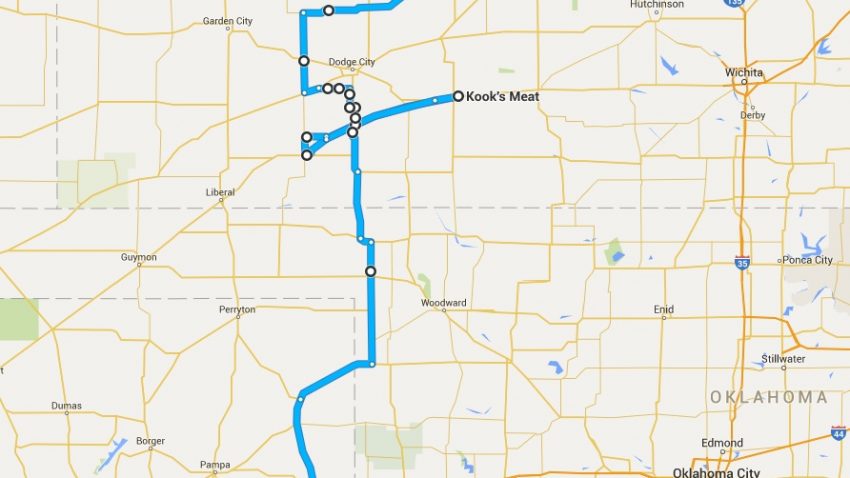

After the storm weakened, we stopped in Hoisington, KS to decide what to do. It seemed that the incredibly messy convection and low shear were causing this day to become unchaseable, and we nearly called a scrub. One cell near Dodge City, where outflow and dryline convergence had produced more organized storms, gave us hope however, and we moved to intercept. Intercept occurred in Hanston, KS, where the storm showed us the closest thing to a tornado we had seen all day (Figure 2) when she showed us a lowered rotating wall cloud. The storm was tornado warned for about 15 minutes, and then lost rotation as it merged with other cells and became a QLCS (quasi-linear convective system).

Figure 2: A lowered, rotating wall cloud is visible on the far right. Taken looking south from Hanston, KS

We raced ahead of the squall line to our hotel in Great Bend, the same hotel we stayed at just two nights ago, and made it there just in time.

We appear to be very close to our target tomorrow in central Kansas, although the passing of the shortwave trough that created today’s low will create some downward motion of the atmosphere which may inhibit strong updrafts.

-Isaac Bowers

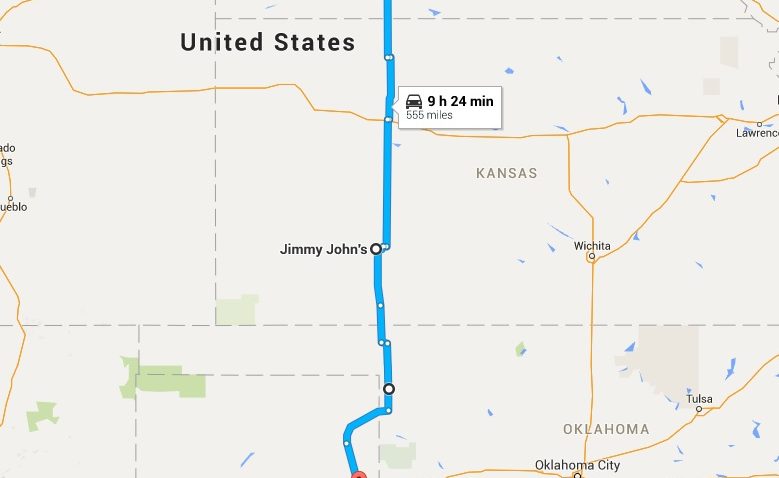

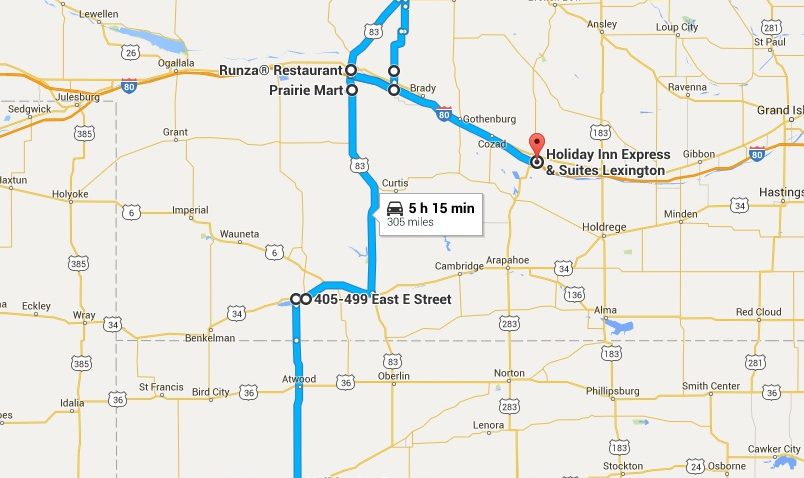

Click this link for an interactive chase map!